|

|

(Click to invert colors, weenie.)

(Requires JavaScript.)

Scroll down for Prelinger stuff Email: darkblogules at yahoo dot com

All email will be assumed to be for publication unless otherwise requested.

What's in the banner?

Father of Bloggers

InstaPundit We. Are. Not. Worthy. James Lileks Your Tour Guides to the Abyss Charles Johnson Damian Penny Intel Rantburg Aussie Oppressor Team Bleah! Punk Author Dr. Frank Insolent Woman Natalie Solent People who still read this blog for some reason Alien Corn Gother than thou Ghost of a Flea Prelinger Stuff Introducing the Prelinger Archive Tuesday in November Make Mine Freedom Prelinger Writes In! Freedom Highway Mental Hygiene The Snob Prelinger's web site The on-line Prelinger Archives Mental Hygiene by Ken Smith |

Sunday, August 27, 2006

Posted

8:57 PM

by Angie Schultz

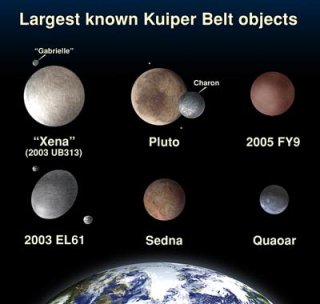

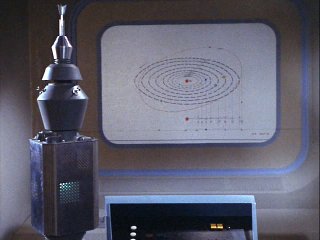

Pluto's Public Click image for Cafepress site. Not affiliated, etc. The furor over the status of Pluto rages on. First the IAU "demoted" it to 'dwarf' planet, and now others say that the vote was "hijacked" (though whether anyone's going to do anything about it is unclear). Meanwhile, the general public has been up in arms over the change. Unfair!  I must say, I don't get it. The most logical explanation for the public's fondness for Pluto is that people grew up knowing that there were nine planets, and they don't want to have to change that tiny, nearly-useless piece of information. But in my experience, people forget scads of things they learned in science class with nary a tremor. And besides, when I was a kid Jupiter had twelve moons, Saturn nine, Uranus five, and Neptune, two. At one time I could have probably named them all. Now I don't even bother to remember how many moons each has, much less what their names are. I have to consult a moon table. So why this passion for Pluto? Up at the top I typed, "I don't get it". But I suddenly think I do. How many people would be protesting at the addition of a planet? What if a tenth planet, say, Neptune-sized, would have been found? Would people be selling T-shirts emblazoned "Nine Is Enough!"? No. So I think what's going on here is that people are a little disappointed in science. Make that Science. The ancients knew only five planets (out to Saturn, and of course didn't count the Earth as a planet). Uranus was discovered in 1781, Neptune in 1846, and Pluto (the Twentieth Century's -- and America's -- own) in 1930. That's Science, people! That's Progress! But now Science has taken a planet back! That's not supposed to happen! We're supposed to advance, to get more planets. What gives? Oh, sure, every once in a while someone trumpets a new planet, but it turns out to be some cosmic pebble, and they give it a name like 2003 EL61, or Quoaoaoaoar.  NASA, ESA, and A. Feild (STScI) People want a real planet, maybe a nice gas giant. Besides, if we don't get a ninth, real planet, a lot of old science fiction shows are going to look awfully foolish, because the humans always showed the aliens (or the psychotic, world-destroying robots) a schematic of a system with nine planets to establish the location of Earth.  And it's not just in science fiction, either.  Whether people realize it or not, this little fracas has been educational. It's not often that most people get to see how Science is done. That is to say, sometimes it's not very scientific. In this case, some astronomers anticipate a number of Pluto-sized objects as larger telescopes allow us to see more objects in the Kuiper Belt, perhaps a very large number. Are these "planets"? The original draft resolution called for a scientific definition: if the oject is self-gravitating (i.e., large enough so that gravity has formed it into a sphere), and if it orbits the sun (rather than another planet), then it's a planet. The problem with that is that it gives us -- -- 11 current planets (including asteroid Ceres and 2003 UB313 aka "Xena") --  Martin Kornmesser -- and an even dozen "candidate" planets  Martin Kornmesser -- for a total of twenty-three planets. And that's just for now! No doubt there'll be more Kuiper Belt objects discovered. Do we really want twenty-three+ planets in the solar system? As far as astronomers are concerned, the answer would probably be: why not? Is there anything fundamentally different about the planets, about they way they were formed? (Actually there is, but we'll get to that in a minute.) But other people might object. For one thing, do kids want to have to remember the names of more than twenty planets, and their order from the Sun? Does anyone find it odd that this is considered a serious objection? At least by scientists? Does anyone else find it odd that the number and positions of the planets is one of those things you have to know to be considered an educated person? (Don't get me wrong. I want people to know about the planets. But why planets rather than, say, the elements and their position in the periodic table? That's much more useful information.) (Then again, a smaller number of planets means the National Air and Space Museum's solar system model won't have to swim -- see the bottom of the article.)

But if we're going to categorize solar system objects, we have to do it scientifically. That is, if we're scientists. That means not deeming Pluto a planet because you shook Clyde Tombaugh's hand, as astronomer Robin Catchpole is quoted as saying in that link (as I'm sure Catchpole knows quite well). That's a human reaction, to want to be part of history -- just as human as to want to keep the universe you grew up with -- but it's not very scientific. If you are going to categorize solar system objects scientifically, then you have to think about what the planets have in common. Do planets have a unique composition? Were they formed in a specific way? You could make a case for excluding objects in the asteroid belt on the grounds that they're not really planets, just dirt that was supposed to form a planet, but never got their act together. (Not strictly a scientific explanation, but close enough.) That cuts our 23 planets down to 19, but of course that will probably rise as more Kuiper Belt objects are found, so it's only a little help. Now, if you really wanted to make a sound, scientific classification as to what is a planet, you'd have to look at what kinds of planets there are, where they gather, and whether there are characteristic sizes of planets. That last would be a really useful measure; if planets fell into distinct size regimes, we might be able to say something about how planets -- as opposed to other solar system bodies -- are formed.

And, as it turns out, they do fall into distinct size regimes! Not only that, but the members of these distinct regimes also have very distinct compositions, and are found in different parts of the solar system! So, obviously, the only logical scientific classification scheme is for Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune to be called "planets", and the smaller bodies (such as Pluto) (oh and the Earth) to be referred to as "dwarf planets". (You saw that coming a mile away, right?) But, I really don't see that happening. I suggest it merely to highlight my point that science doesn't always get done scientifically. On a somewhat ironic note, the IAU 2006 news page shows that the chair of the Pluto vote session was Jocelyn Bell Burnell, who knows from dodgy demotions.  In 1967, she (she was Jocelyn Bell then) and her thesis advisor, Anthony Hewish, discovered pulsars. In 1974, this discovery netted a Nobel Prize in physics -- for Hewish. Bell was not included. She has been publically graceful about this decision. Her career in astronomy since getting her PhD has not been (ahem) stellar. Whether this is cause or effect I cannot begin to speculate. Vanderbilt University astronomer David Weintraub has a opinion piece on the subject here. I must confess I don't quite see what he's trying to say, except that I agree with his statement:

Although I don't see how it'll do them any harm to memorize the planets. (Can you imagine Earth kids on a school outing with kids from another solar system, one that has, say, 50 planets? "Our system has eight planets. How many does yours have?" "Ummm..." "Unthahorsten can't count that high! He doesn't have that many prehensile digits!") But Weintraub once said something nice to me (which people are rarely inspired to do), so I'll point out his article. Also, if you're really fascinated by the topic, you could buy his book. More fun Pluto facts here. Pluto was named by an 11-year-old girl, Venetia Burney, whose grandfather was Librarian at the Bodleian Library at Oxford. She was still alive as of a few months ago. Interestingly, her great-uncle had named Mars's moons, Phobos and Deimos. In January, NASA launched the "New Horizons" mission, which will get to Pluto in 2015. Some of Clyde Tombaugh's ashes are on board.

|